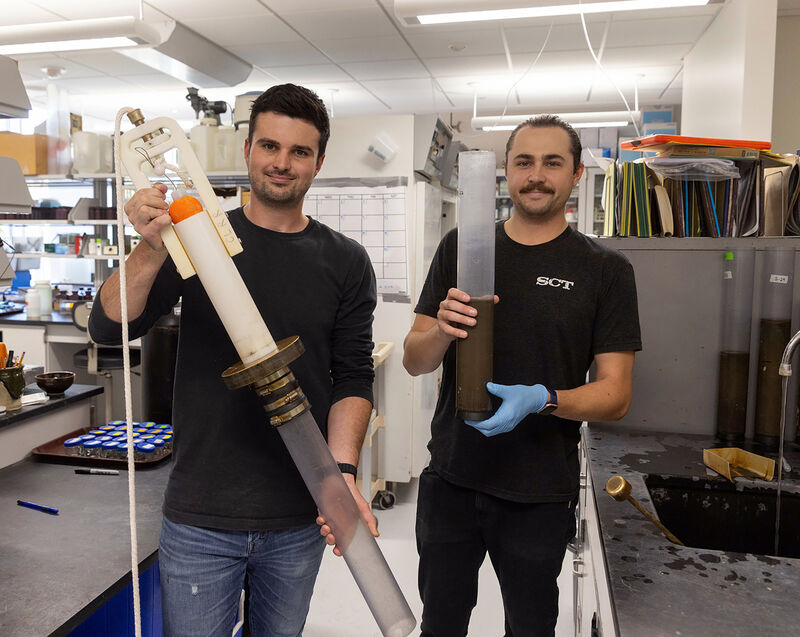

CLRR Field Coordinator Andrew Schneyer, left, and Laboratory Coordinator Conor Dougherty show a gravity coring device like the one used to take sediment cores on Green Lake in Wisconsin. Conor is holding an intact sediment core.

Menomonie, Wis. — Covering more than 7,600 acres, Green Lake is one of Wisconsin’s largest and best-known natural, inland lakes. It’s also the deepest such lake in the state, at 236 feet.

The 1,000 members of the Green Lake Association rightly take pride in their important local and state resource, in southeastern Green Lake County. The lake has a rich Ho-Chunk tribal history, and users enjoy two beaches, eight boat launches, 44 miles of shoreline and angling for its 40 species of fish.

GLA members also are rightly concerned. Building over decades, a problem with excess phosphorous at two inlets, the Silver Creek Estuary and the County Highway K Marsh on opposite ends of the lake, has been getting worse. Phosphorus acts as a fertilizer and spurs plant growth.

Green Lake had two beach closures last summer because of toxic blue-green algae blooms and another six-week bloom in the marsh. GLA is working to reduce the phosphorus and hopefully the toxic blooms by turning to a state and national leader on the issue, the Center for Limnological Research and Rehabilitation — CLRR — at University of Wisconsin-Stout.

“The Green Lake Association is being proactive. They’re doing the right thing. These are the lakes that can be managed. Let’s nip it in the bud,” said Bill James, CLRR founder and director.

Based on state standards for water quality, Green Lake’s degraded water quality already has resulted in it being listed as “impaired.”

“People are noticing the lake is changing,” said Stephanie Prellwitz, chief executive officer of the Green Lake Association, who noted that the algae bloom in the marsh was the first she’d seen in her 11 years with GLA.

“The lake is giving us warning signs. For a gem of a lake like Green Lake, it’s important we take the necessary steps to reduce phosphorus sooner rather than later. It’s time to step back and plan how to tackle a challenge of this magnitude,” Prellwitz said.

Along with best management agricultural practices, such as no-till farming and cover crops, that can help reduce phosphorus in the watershed, “What new tools can we bring to the table to sequester phosphorus from these inlets?” she said.

Warmer winters this century likely aren’t helping. Since regular lake monitoring began in 1939, Green Lake has frozen in the winter all but three times, but two have been in the last three years. Plus, Green Lake is staying frozen about a month less each winter compared with 1939.

Warmer water is “allowing lakes to biologically cook for longer, and algae is taking full advantage of it to grow,” Prellwitz said.

Along with CLRR, which is providing testing and scientific expertise, GLA is working with Stantec, a sustainable engineering consulting firm, to address the issue.

Sediment cores and analysis

Eighty percent of phosphorus entering Green Lake flows through its two main inlets. Over time, phosphorus has built up in the sediment of the inlets. It feeds plant life, like algae and duckweed, and depletes oxygen in the water. This causes a chain reaction of sorts, with excess phosphorus diffusing from the sediment, moving into the lake and reducing water clarity.

“We’re not hitting our long-term goals. We need a 60% reduction in phosphorus just to remove the lake from the impaired waters list,” Prellwitz said.

CLRR analysis by James will indicate the rate of phosphorus diffusion. Analysis on 24 sediment cores, taken in summer in and in early fall, are being conducted by CLRR employees Conor Dougherty, lab coordinator, and Andrew Schneyer, field coordinator, in the CLRR lab in UW-Stout’s Jarvis Hall Science Wing.

Long cylinders were plunged into the creek and marsh bottoms at four stations to extract the cores.

In the lab, the sediment is tested with and without oxygen to determine how much phosphorus is released. Once the rate is determined, James and a science advisory panel assembled by GLA will analyze the data and provide recommendations to treat the estuaries. More research could be necessary in 2025 before any action is taken.

“Bays are manageable. One of our goals is to try to stop what’s coming into the lake,” James said.

James was a research aquatic biologist for 32 years in Spring Valley — Pierce County — with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineer Research and Development Center, Environmental Laboratory – Eau Galle Aquatic Ecology Laboratory.

“Bill is a leading expert who has advanced how we measure internal loading in sediment,” Prellwitz said.

James has a master’s degree in limnology from Kent State University and has taught an undergraduate course at UW-Stout in Aquatic Ecology and Management and a graduate course in Advanced Limnological Approaches.

UW-Stout has an undergraduate program in environmental science, with a concentration in aquatic biology.

CLRR is a center located within the UW-Stout Office of Corporate Relations and Economic Engagement.

Other CLRR lake projects

While a treatment plan for Green Lake is to be determined, CLRR is using alum, a natural compound, to manage water quality in six state lakes that are listed as impaired:

- Half Moon, in Eau Claire

- Cedar, Long, East Balsam and Big Round, in Polk County

- Big Doctor, in Burnett County.

CLRR sediment testing has supported other lake projects in Wisconsin and Minnesota.

Except for Big Doctor Lake and Cedar Lake, the treatments have been highly successful in mitigating the problem. Ongoing testing is conducted on each lake to adjust treatments as needed; a new approach may be needed on Big Doctor and Cedar, James said.

“These lakes are big, complicated ecosystems. It’s not a cookbook recipe,” James said.

Solitude Lake Management, a Florida company with an office in St. Paul, applies alum in the lakes based on CLRR’s analysis.

CLRR was created to help lakes meet state standards for levels of phosphorus and chlorophyll in the water and for water clarity, to stop algae blooms and improve recreation.

“There’s a purpose to this — preserving the beauty of Wisconsin Lakes. It’s one lake at a time,” James said. “It’s human-driven — we create the problem and have to solve the problem.”

UW-Stout is Wisconsin’s Polytechnic University, with a focus on applied learning, collaboration with business and industry, and career outcomes. Learn more via the FOCUS2030 strategic plan.

Add new comment