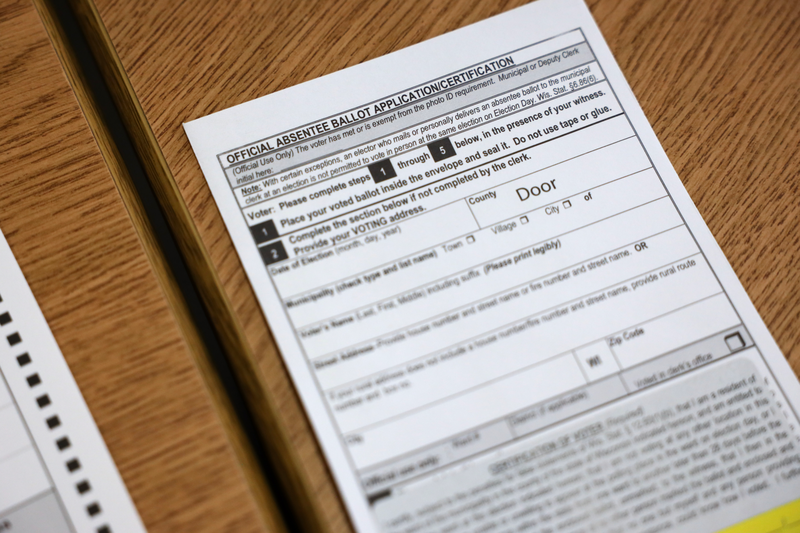

An absentee ballot envelope for the Nov. 8, 2022, election is seen at the village of Ephraim administration building in Door County, Wis., on Oct. 25, 2022. (Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

A lawsuit that could complicate Wisconsin’s absentee voting process, create additional last-minute work for election officials and confuse voters is coming before a Marinette County judge Wednesday.

The lawsuit asks Marinette County Circuit Court Judge James Morrison to require voters who request their ballot through MyVote, Wisconsin’s online voting portal, to return a signed copy of their request with their actual absentee ballot for their vote to count.

Additionally, the lawsuit asks Morrison to bar election officials from using a redesigned absentee ballot envelope that states the envelope is an original or copy of voters’ original absentee ballot request — something that the lawsuit alleges is not the case.

The Wisconsin Elections Commission urged the court to reject those requests in a Friday filing. But even if Morrison were to grant the requests, the commission asked him not to require any changes ahead of this year’s elections because they “would risk disenfranchising tens or even hundreds of thousands of Wisconsin voters in upcoming elections,” something the commission said would be “a stunningly undemocratic result.”

The requested changes to Wisconsin’s absentee ballot voting system would add work for clerks ahead of their June 27 deadline to begin mailing absentee ballots for August’s primary elections. Morrison may be sympathetic to the requests, considering that he granted a temporary injunction May 17 prohibiting the Wisconsin Elections Commission from requiring local clerks to use the redesigned absentee ballot envelope.

Thomas Oldenburg of Amberg filed the lawsuit. He’s represented by two attorneys who have been central to efforts casting doubt on the state’s election results.

One of them, Kevin Scott, represented former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman, who led a costly but fruitless partisan review of Wisconsin's 2020 election, in a lawsuit that sought to jail the mayors of Madison and Green Bay if they didn’t sit for an interview about the election. The other attorney, Daniel Eastman, asked a federal court to decertify Wisconsin’s 2020 presidential election results.

The lawsuit was filed because “Wisconsin needs to demand fair election administration,” Eastman said at a May 20 press conference in Union Grove. “It has to be done right. It has to be done according to law.”

But critics say the lawsuit is one of many filed since the 2020 election that seeks to make voting harder.

The litigation “seems to be part of an ongoing effort to make what are now technical requirements into substantive hurdles for absentee voters,” said Mike Haas, Madison’s city attorney and the former administrator of the Wisconsin Elections Commission.

The lawsuit’s first argument is rooted in a state statute, enacted in 2006 but since modified slightly, that says voters do not need to provide a signature when submitting their absentee ballot request electronically, but they “shall return with the voted ballot a copy of the request bearing an original signature of the elector.” MyVote has been available since 2012.

When a voter requests a ballot using MyVote, it generates a copy of a standardized request form that is shared via email with the voter’s municipal clerk, according to a WEC official’s testimony submitted in a separate case. The lawsuit contends a copy of that request form must be included in the absentee ballot envelope, alongside the completed ballot, in order for it to be counted. If the form is not included, the lawsuit argues, that ballot should not be counted.

The redesigned envelope is intended to serve a “dual purpose as an absentee application and absentee certificate,” according to materials prepared by WEC’s nonpartisan staff for an August 2023 meeting where the commissioners approved the new design. The new envelope fulfills statutory requirements for both in-person absentee voters and voters who cast their absentee ballot by mail, staff wrote.

In a Friday filing, the election commission said the plaintiffs were incorrectly interpreting “copy” to mean “duplicate,” adding that the form is indeed a copy because it contains all the information needed to identify the voter and confirm they requested a ballot.

The new design was “put through extensive rounds of testing, with serious consideration given to ease-of-use, accessibility, and compliance with state law,” WEC spokesperson Riley Vetterkind said in a statement. “An extensive audit of absentee processes and materials by the Legislative Audit Bureau did not identify any problems with the absentee certificate envelope’s dual purpose, nor did prior court decisions that have involved the absentee certificate envelope.”

The suit’s second claim is based on a line on the state’s redesigned absentee ballot envelope that states: “I requested this ballot and this is the original or a copy of that request.”

The lawsuit argues the ballot is not the original or a copy of the request voters submitted to receive their absentee ballot and therefore would require Wisconsin voters to make a false statement if they sign the form. Accordingly, the lawsuit says, the judge should bar clerks from using the envelopes.

The commission also argued that Oldernburg doesn’t have standing to bring the legal challenge.

“At best, (Oldenburg) has a quibble with one line of language on a WEC form — but that narrow quarrel cannot support the much broader declarations he seeks about how absentee voting laws should be interpreted and applied,” the commission said in its court filing.

If the judge agrees with the lawsuit’s arguments, local election officials could need to print copies of each absentee ballot request form they receive from MyVote and include it in the envelope alongside a voter’s absentee ballot. That could create additional last-minute work for election officials ahead of the August primary. It could also require voters to complete another step in order for their absentee ballots to be counted.

“Absentee ballot requests have increased so much, even just since COVID-19,” Marinette Deputy City Clerk Mindy Campbell said. "Marinette has 10,000 people, and before COVID-19 we used to have between 100 and 200 absentee ballot requests. This April, there were 500 requests, and that’s for a low-turnout election.”

"So to find everybody's absentee request, print it off, make a copy — it's another thing to fold and shove into an envelope. It is a lot, but it's possible,” she said, adding that the task could be more challenging in bigger cities like Milwaukee and Madison.

Forward is a look at the week in Wisconsin government and politics from the Wisconsin Watch statehouse team.

This article first appeared on Wisconsin Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Add new comment