This is the first in a series of articles about public health and COVID-19 from Alexandra Hall, M.D. Dr. Hall is a physician in Student Health Services at UW-Stout where she also teaches in the Biology Department. You can learn more about Dr. Hall at her profile page.

Q: How can a cloth face mask work when the virus is small enough to fit through the holes in the cloth?

A: It’s true that the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 is very small, about 0.1 microns or 100 nanometers. (A micron is one-millionth of a meter.) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7224694/ Depending on the cloth used, sometimes the openings in fabric are as large as 20 microns, which you would think then couldn’t be effective at stopping COVID-19. Luckily for us, this virus doesn’t float out into the air by itself. Instead, it travels on and within the bits of moisture that leave our mouths and noses when we breathe, talk, laugh, shout, sing, sneeze, and cough. Those bits of moisture in which the virus travels are called respiratory droplets and aerosols, and they range in size from less than 1 micron to over 100 microns (such as the big bits that come out when you cough or sneeze). So, some of them can’t fit through the mask at all, but some theoretically still could.

The interesting thing we’ve been able to demonstrate in laboratories, however, is that most of these moisture particles still can’t get through, and the reason for that is fluid dynamics. Imagine a stadium full of sports fans. Each individual person is small enough to fit through the exit doors, but if they all try to leave at once, it gets jammed and backed up. The same thing happens with these respiratory particles – although many of them could squeeze through the holes in the fabric if they went calmly one at a time, when we breathe or talk they’re instead all coming toward the mask at once; it’s too fast and things get backed up. Then they lose their speed and tend to just stick to the inside of your mask. If you also happen to have a two- or three-layered mask, then very few particles can get through at all, as the holes don’t line up exactly from one layer to another and there’s no straight shot for the lucky few particles that might otherwise get out.

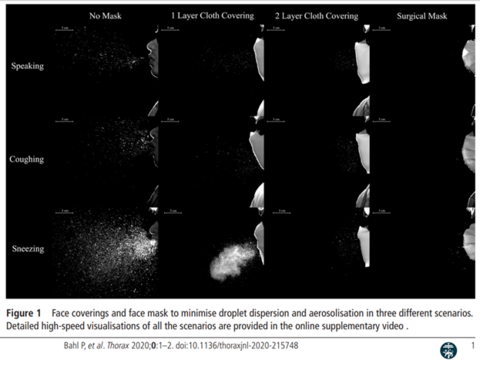

Scientists have studied this in the laboratory in several ways. They’ve done experiments using laser technologies to “see” and capture video and photographs of these tiny respiratory droplets and aerosols when people breathe, talk, and cough through a mask. These have shown that even a simple cloth face mask can greatly reduce the number of respiratory particles that get through. In the image below, you can see images of someone speaking, coughing, and sneezing with no mask, a 1-layer cloth mask, a 2-layer cloth mask, and a surgical mask. As you can see, wearing any type of mask is better than none, and a 2-layer mask is significantly better than a single layer one.

Image

Other studies use a special injector and shoot standardized moisture particles at different types of masks. One of those studies found that on average, homemade cloth face masks prevented more than 80% of small (< 0.3 micron) particles from getting through and stopped more than 90% of the particles that were over 0.3 microns. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.0c03252

Fortunately, too, a mask doesn’t always need to block particles 100% to be effective at reducing spread of the virus. The amount of virus that someone is exposed to makes a difference in terms of whether or not they will get infected and, if so, how sick they may get. So, any reduction in the amount of virus that gets out into the air around us is helpful.

It’s true that the virus is small enough to fit through holes in a mask. Luckily for us, however, that isn’t how it travels. The respiratory droplets and aerosols in which it travels are much larger and can’t fit through the holes in a fabric face mask when they’re coming at it quickly, such as when we breathe or talk. This is how cloth face masks work to help prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Memberships

Alexandra Hall M.D. – Dr. Hall earned a Bachelor’s of Science in Science Education from New York University, taught high school in East Harlem, and then earned her M.D. from Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

She then completed a residency in Family Practice and served as Chief Resident at the University of Vermont. After practicing medicine for Dean Health System in Wisconsin and then at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, Dr. Hall moved to Menomonie, WI to work at UW Stout, where she currently teaches for the Biology department and serves as a physician at Student Health Services.

Dr. Hall has a passion for educating people about health and science; she gives workshops regionally and nationally on various medical topics to both lay and professional audiences and has won several teaching awards for her work.

Add new comment