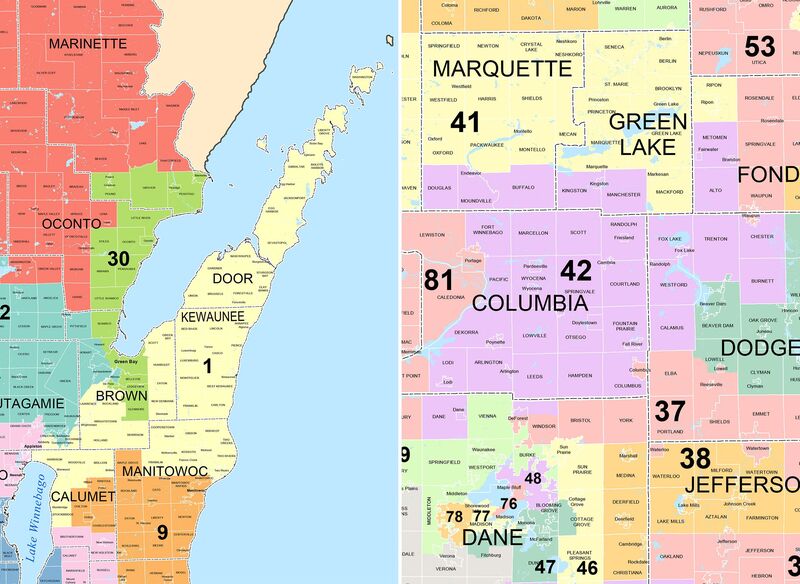

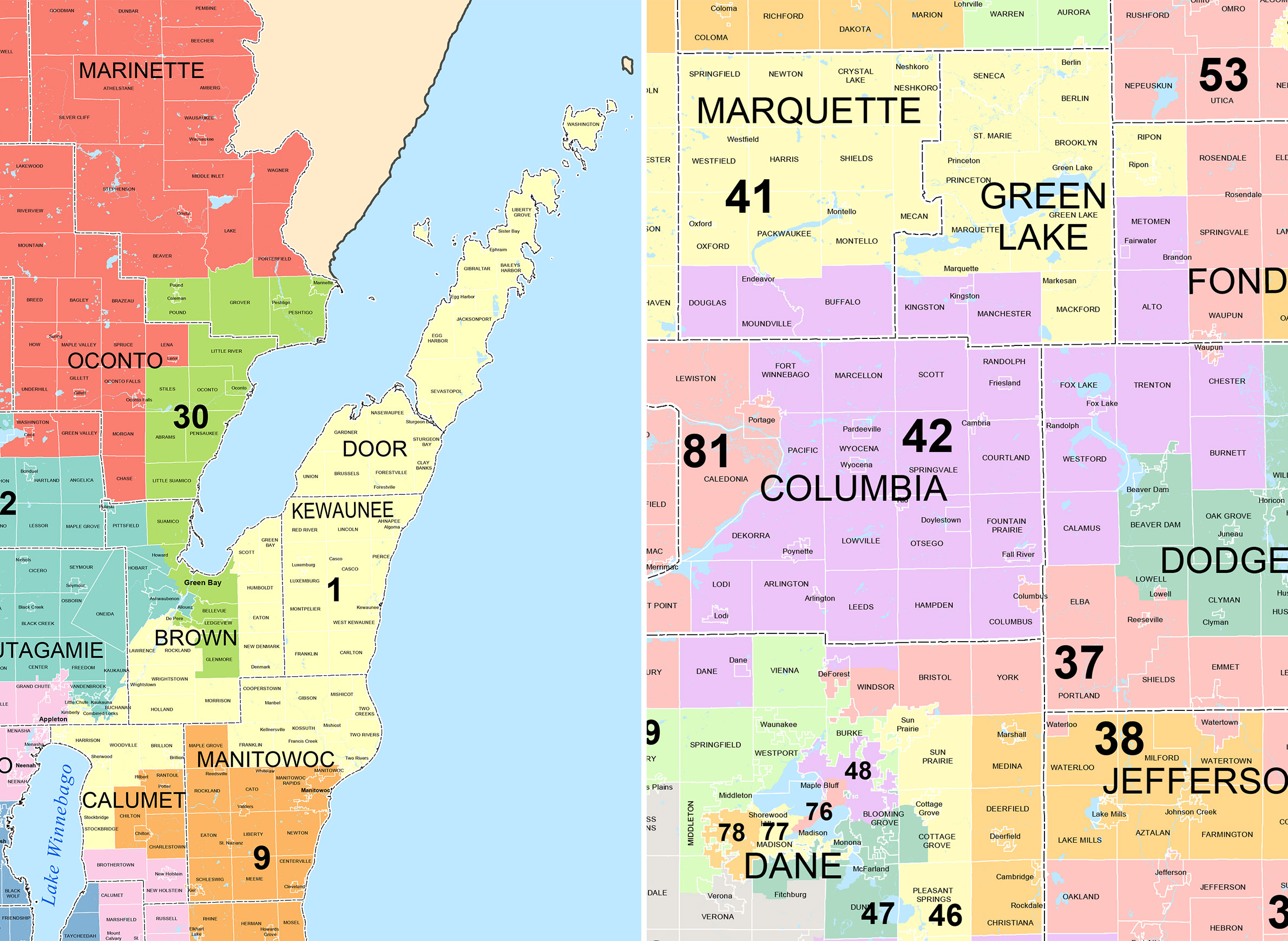

In Newton v. Walker, filed in Dane County Circuit Court on Feb. 26, 2018, voters in the state Legislature's vacant 1st Senate District and 42nd Assembly District are trying to convince a judge that state law requires Gov. Scott Walker to call special elections in those districts. When those vacancies opened at the end of 2017 after Walker hired the officeholders to work in his administration, he refused to call special elections and instead decided to leave the seats unfilled until the Nov. 6, 2018 general election.

In a major break from the behavior of modern Wisconsin governors and even Walker's own previous actions on special elections, this decision will effectively leave both seats vacant for a little over a year.

What happens next will depend on how Dane County Judge Josann Reynolds rules in two questions: Is this an appropriate situation for courts to force a governor to take a specific action, and does state law in fact require a governor to hold a special election before November under these specific circumstances?

A question of standing

In the political arena, the lawsuit is about a lot of issues — whether Walker is violating voters' rights by not calling special elections, whether Republicans are protecting themselves from a Democratic backlash against an unpopular GOP president, what kinds of representation constituents will miss out on even if the legislature isn't voting on bills. But legally, it's about some fundamental questions of state law, and courts may have to wade into some uncharted territory to settle them.

The lawsuit has been framed in media coverage as a battle between Walker and former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, who served under the Obama administration. Holder is indeed the chairperson and public face of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, a political advocacy organization affiliated with the Democratic Party that campaigns against Republican efforts to gerrymander state voting maps, which is sponsoring the lawsuit. But the specific plaintiffs in the suit are eight voters who reside in Wisconsin's two open state legislative districts.

A Walker spokesperson's assertion to reporters that the special elections lawsuit is about how a "D.C.-based special-interest group wants to force Wisconsin taxpayers to waste money" misrepresents the way these types of lawsuits actually work.

This case requires the involvement of people who are directly affected by the lack of special elections in these specific districts, and they have to be willing to sign on as plaintiffs. The National Democratic Redistricting Committee is paying the legal fees and doing the heavy lifting of filing the lawsuit, and working with a law firm with deep ties to the Democratic Party, but there's a long history of advocacy groups and plaintiffs finding each other to fight for a cause in court. The fact that out-of-state attorneys and a national interest group are involved in the case doesn't alter the fact that the lawsuit centers around the interests of actual Wisconsin voters.

Indeed, neither Eric Holder nor the national Democratic Party could successfully sue the governor of Wisconsin by their lonesome in this case. Rather, a simple issue in civil lawsuits called "standing" requires the involvement of voters from the vacant districts.

"You need to have a plaintiff who's suffering what the U.S. Supreme Court would call an injury in fact," said Robert Yablon, a professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School. "This is in state court, but the state rules are going to be roughly similar … the people who've been concretely injured here are the ones who live in the districts."

In this case, eight plaintiffs signed on, five from the 42nd Assembly District and three from the 1st Senate District. The initial complaint spells out their standing by going through them one by one, pointing out which district they live in, noting they are registered voters, and noting that their district has been unrepresented in the Legislature since December 29, 2017. The complaint looks to further establish their standing by contending that each plaintiff "has a clear legal right to the opportunity to elect a Representative to the vacant seat in a special election, which must be called by the Governor 'as promptly as possible' by issuing a writ of election."

Splitting hairs in state law

The plaintiffs' argument in Newton v. Walker is relatively simple: State law requires Walker to call special elections. The plaintiffs are asking the court to compel the governor to do so by issuing a writ of mandamus. Cornell Law School's Legal Information Institute defines it as "an order from a court to an inferior government official ordering the government official to properly fulfill their official duties or correct an abuse of discretion."

The plaintiffs' case mostly hinges upon a particular part of the law governing Wisconsin's special elections, section 8.50 of state statutes. This language reads: "Any vacancy in the office of state senator or representative to the assembly occurring before the 2nd Tuesday in May in the year in which a regular election is held to fill that seat shall be filled as promptly as possible by special election."

Because both the regular election for both vacant legislative districts was scheduled to take place on Nov. 6, 2018, and both vacancies opened up before May 8, 2018, the plaintiffs think it's pretty clear-cut that they have a "clear legal right" to vote in special elections. And a "clear legal right" is one of the conditions that must be met for a court to issue a writ of mandamus.

Another requirement for a writ is establishing that the plaintiffs "will be substantially damaged by nonperformance" of the action they seek to compel the government to carry out. To that end, the plaintiffs' lawyers offer the following argument in their complaint: "Governor Walker's refusal to promptly issue writs of election has already deprived Plaintiffs of representation for the first seven weeks of 2018, and that substantial injury will continue unless and until Governor Walker is ordered to comply with his clear legal duty to call a special election to fill the vacancies."

Perhaps to bolster that sense of injury, the complaints also point out that the eight Wisconsin voters acting as plaintiffs will lack representation not just in the Legislature's regular session, but in the special sessions the governor has the power to call. Since staking out his position on special elections in the two vacant districts, Walker has called two special sessions. One, aimed at restricting access to public benefits like food stamps, is already completed. Another that would be centered on a package of bills dealing with school security was called on March 15, a couple weeks after the lawsuit was filed.

Both in and out of court, Walker is sticking to his position.

Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel filed a response on March 7 that makes the same arguments the governor and his spokespeople have proffered since originally announcing no special elections would be called: The wording of state law doesn't technically require a special election because both the seats were vacated in calendar year 2017; holding special elections would cost money; and, if special elections were called, it would be impossible to seat the new officeholders before the Legislature's schedule of floor debates and votes wraps up for the year.

Walker and Schimel have emphasized language in the statue that reads "in the year in which a regular election is held." They claim that since regular elections are scheduled in both vacant districts in 2018, but the vacancies occurred in 2017 (on December 29, the last weekday of that year, to be precise), the law lets the governor off the hook for needing to call a special elections.

In the course of making these arguments, Schimel contends that the plaintiffs haven't met the conditions for asking the court to issue a writ of mandamus. One point in the response is even headed with the statement that "Plaintiffs' [sic] have no clear legal right to elect new representatives in special elections," and argues that Wisconsin voters "only have the right to vote in special elections in specific circumstances and none are applicable here."

Schimel's response filing points out that statute 8.50 specifically mentions one purpose of filling a legislative vacancy. "The special election to fill the vacancy shall be ordered, if possible, so the new member may participate in the special session or floorperiod," reads one portion of the statute.

Schimel goes on to argue that this means that "the Legislature has acknowledged and accepted that there will be times when Wisconsin citizens may be unrepresented in the legislature." In other words, Schimel is saying that the state can leave a legislative seat vacant for a while if filling it sooner wouldn't meet the express purpose of having an officeholder present to debate and vote on bills.

But the fact that Walker called the school-security special section after Schimel filed this response may undercut that argument before the court. It may or may not have been practical to elect and seat new members for the vacant districts in time for this latest special session, and state law places conditions on the timing of special elections. However, Walker's decision to call multiple special sessions does bolster the plaintiffs' argument that they won't have representation in the Legislature during debate and voting over significant legislation.

In a response to Schimel filed on March 12, the plaintiff's lawyers argue that the case comes down to a single issue. They argue Walker's position "defies the plain language of the statute and leads to absurd results" because the vacancies still occurred before the second Tuesday of May in 2018, and that whether or not they occurred before the start of the new year is immaterial.

One novel aspect of what the plaintiffs are asking for is related to the timing of special elections. State statute requires a special election to be held between 62 and 77 days after the governor calls it. In their lawsuit, though, the plaintiffs want the governor to call elections immediately, and for these elections to be held within five weeks. Schimel points out in his response that if the court orders this action, it would go against state law.

The plaintiffs' Madison-based lead attorney, David Anstaett of the law firm Perkins Coie (whose major clients have also included the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton's 2016 presidential campaign) did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story, nor did a spokesperson for the Wisconsin Department of Justice.

The timing dilemma

The request for quicker-than-usual special elections probably reflects an awareness on the part of the plaintiffs that they don't have a lot of time to get what they want. If a court battle drags on until fall, then the seats wouldn't get filled until the regularly scheduled November 2018 election, which is what Walker wants. The outcome of the lawsuit would then be meaningless, aside from perhaps offering some legal precedent that could help in future disputes.

"In situations like this the clock can sometimes just run out," UW law professor Robert Yablon said.

While there isn't a massive body of jurisprudence around special elections, this very issue of timing has previously plagued people suing for special elections to be called. In these cases, plaintiffs are often working with an interval of just a few months before an election would take place anyway.

One parallel is ACLU of Ohio v. Taft, filed in U.S. District Court in 2002.

In this case, Ohio Governor Bob Taft, a Republican, said he would not call a special election to fill the seat of Democratic Rep. James Traficant, who was expelled from the U.S. House of Representatives in July 2002 in the wake of a major corruption scandal. Like Walker, Taft argued a special election would cost too much. He also claimed that because Traficant's district had been significantly redrawn that year during the state's decennial redistricting process, voters would be confused. The ACLU of Ohio sued Taft and eventually prevailed in court. The ruling didn't come down until 2004, though, so Traficant's old seat was filled in the regularly scheduled November 2002 election, as Taft originally desired.

A similar example can be found more than a decade later in Missouri. In 2014, a group of Show-Me State voters and Republican Party activists sued Democratic Gov. Jay Nixon to compel him to call special elections in four vacant state legislative districts, one of which sat vacant for nearly a year and a half. After the lawsuit was filed, Nixon ended up calling special elections. A state court then dismissed the case without addressing the state-level constitutional issues the plaintiffs were trying to raise.

Ultimately, in this case, the plaintiffs got their elections, but no answers from the court system as to how Missouri governors should apply that state's laws in dealing with future legislative vacancies. And even if the court had issued a ruling, it wouldn't be very useful in Wisconsin.

In Newton v. Walker, circumstances of timing will require the court to make a decision that could significantly impact not only politics in 2018, but also the way Wisconsin treats legislative vacancies long into the future.

Editor's note: This item is corrected with an updated reference to Robert Yablon.

What's At Issue In Wisconsin's Special Elections Lawsuit was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

Memberships

Steve is a member of LION Publishers , the Wisconsin Newspaper Association, the Menomonie Area Chamber of Commerce, the Online News Association, and the Local Media Consortium, and is active in Health Dunn Right.

He has been a computer guy most of his life but has published a political blog, a discussion website, and now Eye On Dunn County.

Add new comment